A nearly-forgotten dog species which went extinct in the 19th century was once a crucial part of coastal Indigenous life.

A new genetic study looking at the coastal wooly dog was published this week in the journal Science. It confirms coastal Indigenous people were making wool blankets from dog hair long before settlers brought sheep to North America.

The study examined the genetics of the only known purebred pelt in existence, taken from a dog named Mutton in 1859 who died of an illness, and currently stored in the Smithsonian. It also looked at archaeology, history, and traditional Indigenous knowledge to try and find out why the dogs, which were part of Indigenous cultures for millennia, died out.

The study concludes the main reason for their disappearance was because of 19th century colonial policies. Machine-made textiles played a role, but the dog was too important for coastal Indigenous people to abandon thousands of years of selective breeding and cultural integration. The dogs were prized, often kept in special enclosures by women who harvested their curly, wooly hair to make blankets. A few examples remain, including some made with dog and goat hair, providing evidence of the range of indigenous trade routes from the coast to the Interior.

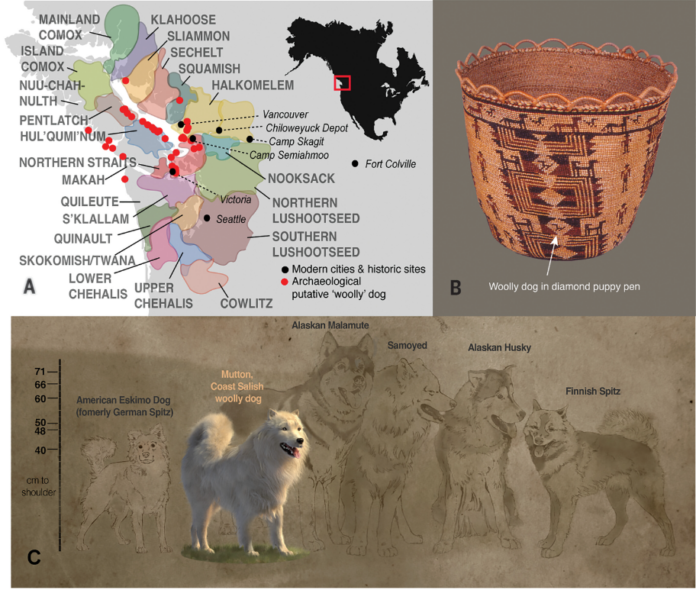

The woolly dogs were known as “sqwemá:y,” “ske’-ha,” “sqʷəméy̓,” “sqwbaý,” and “q’əbəɫ” in some Coast Salish languages. Current evidence shows their range was from central Washington State all the way to Campbell River.

The woolly dogs were known as “sqwemá:y,” “ske’-ha,” “sqʷəméy̓,” “sqwbaý,” and “q’əbəɫ” in some Coast Salish languages. Current evidence shows their range was from central Washington State all the way to Campbell River.

“Given their role in Coast Salish societies, it is unlikely that the entire dog-wool tradition would have been abandoned simply because of the ready availability of imported textiles,” reads the study. “Furthermore, this explanation ignores weavers’ efforts to maintain culturally relevant practices in the face of settler colonialism. The use of blankets and robes served not only a functional purpose but also a spiritually protective role in Coast Salish cultures. Wearing a ceremonial blanket was spiritually transformative because it intertwined the creator of the blanket, the wearer, and the community.”

The study points out the dogs were a form of wealth and status for Coast Salish women, “who carefully managed the dogs to maintain their woolly coats, isolating them on islands or in pens to strictly manage their breeding. Island names often reflect their connection with dogs, such as “sqwiqwmi’” (“Little Dog”) village on Cameron Island in Nanaimo.”

Waves of settlers and miners from the 1858 Fraser River Gold Rush onwards devastated Indigenous communities on the coast, leaving them unable to maintain the dogs and keep them from interbreeding with European-origin animals.

“Survival of woolly dogs depended upon the survival of their caretakers,” says the study. “In addition to disease, expanding colonialism increased cultural upheaval, displacement of Indigenous peoples, and a diminished capacity to manage the breed. Policies targeted Indigenous governance and inherent rights, resulting in the deliberate disenfranchisement and criminalization of Indigenous cultural practices.”

As Indigenous women, the caretakers of woolly dogs and weaving knowledge, suffered, so did the dogs. The study shows that as Indigenous women became marginalized in society through policies and legislation such as the 1876 Indian Act, which explicitly denied them property rights, the dogs slowly disappeared.

By the 1950s and 1960s, there remained little evidence they had ever existed, except for a few blankets and stories. Recent genetic research and archaeology has renewed interest in the wooly dog’s history, and this week’s study provides a host of new evidence for the species’ essential role in pre-contact coastal Indigenous cultures.